What follows is a repost from Motionographer, published October 25, 2017 by JOE DONALDSON during his time as editor.

Editor’s note: The chances are that you’ve seen Adam Plouff’s handy work before. I’d wager that he’s responsible for 9 out of the 10 noodle arm characters you see on a daily basis via his tool RubberHose. All jokes aside, Adam’s effect on the industry has been huge. He is an amazing tool maker and is constantly working to make our lives easier. His latest tool Overlord is a testament to just this. In this Motionographer guest post, Adam gives a sobering look at what it’s like getting called up to the big leagues, then reassessing what matters most when life happens.

Background

Like a lot of the people I meet who animate things for TV and the internet, I spent my adolescence playing in loud bands, designing t-shirts and piecing together ugly flash preloaders and myspace pages. After earning a prestigious Associates Degree in TV production from community college (not in Art, Design or Computer Science, but multi-camera shooting and knot tying), I spent the next 9 years cutting broadcast promos for Cartoon Network, TBS and TNT. After a few years in TV, I began to reduce the number of hours I slept in order to work on personal projects that I actually enjoyed.

I have always been ok with separating client work from passion projects. Working, no matter how unglamorous the work, gives you a chance to explore and find the kind of projects you want to be a part of. It can also be helpful when you have absolutely no idea what you’re doing. While generating hours of content for viewers to fast-forward through, I developed a strong sense for rigging up expressions into network toolkits that would eventually save myself a lot of time. This extra time freed me up for more personal work. I learned from personal projects that I like animating, and from client work that I enjoy building systems.

In 2014 I was introduced to the idea of alternate revenue streams and passive income by my former studio-mate, Michael Jones, while he was launching Mograph Mentor. My cashflow had always been directly linked to hours worked. Freelancing for the right industries can earn you a lot of money from high hourly rates, but no matter how much you bill, taking a week off work still means you don’t get paid.

Building Rubberhose

Just for clarity, I have no formal education in programming. In the summer of 2014, my family and I were on vacation in Charleston the same week Sander released Ouroboros v1. On the detailed writeup it had a note about learning Javascript from Codecademy. So while my toddler child forced us to take mid-day naps, I excitedly spent time on my phone in lessons about loops and conditional statements.

Along with building some more robust expressions for clients, this new knowledge allowed me to draw geometry in a lot of new ways. One of these methods was for cleanly constructing straight lines between points. It took a lot of duplicating and manual setup to use, but I realized this setup was basically a linear list of instructions that could probably be automated as a script. So if I learned how to write a script I could have something.

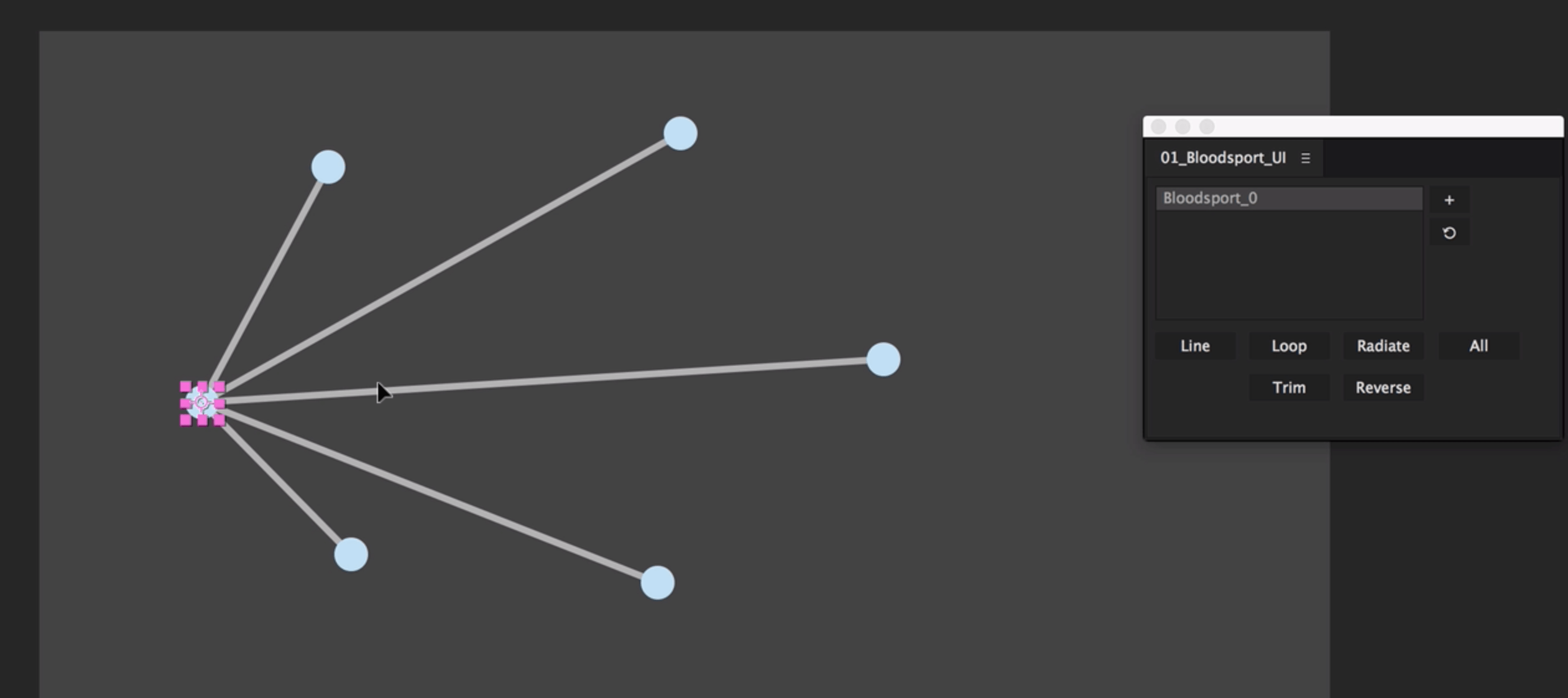

After watching a bunch of video tutorials I built a really nasty panel that had a couple buttons on it that would trigger this line drawing system. I called it BloodSport because this is the face I make (even now) whenever I figure out code stuff:

I immediately took a really low paying project that had a lot of animated charts and lines to test BloodSport on. It failed miserably and using it in production created more work for me. But I focused on one particular shot that had a really sharp movement that would benefit from motion trails. I attempted to use a BloodSport line and sample back a few frames to dynamically draw a line trail based on where an object had been. I was optimistic, but using straight lines to replicate motion arcs looked awful.

I tried a lot different of solutions, but drawing curved lines was a lot harder than I thought. During this process I discovered an underused shape layer type called a PolyStar and thought maybe if I worked out the right math, I could control its shape. A bit of time on Khan Academy taught me enough Trigonometry to get started.

I packaged this up into what I thought could be a commercial script, but it was buggy and wasn’t accurate enough to be sold as a motion trail system, so I abandoned it.

Months later I took a job requiring a dozen noodle-arm characters. The animation timeline was short and I needed a way to rig and animate with a much higher degree of flexibility than most rigging methods would allow. So I gave myself one full day to try and repurpose the bendy line math from motion trail system into a bendy arm/leg system. It barely worked for the project but saved me a lot of time overall.

Nailing down a shot is a great feeling, but tricking a calculator machine into drawing art for you is completely addicting. Over the next few months, I built this bendy line code into version 1.0 of the RubberHose rigging system. I didn’t know anything about UX or how to do simple things like building icons into a panel. Even after preorders had started, my beta testers were finding major bugs that would fully crash After Effects. I had no idea what I was doing but was learning so much every day by building and thanks to the generous sharing of other devs. I stopped sleeping for a while but eventually had a usable product.

The response was a lot stronger than I expected, and it helped a bunch of motion designers struggling to integrate characters into projects or just get started in character animation. I didn’t plan on making a character rigging tool and failed at everything I tried to build before something worked. After a year of building weird things out of curiosity, I now had an additional revenue stream. It felt good to not be fully dependent on client work. I could, for the first time, begin to think about what the next step of my work-life might be.

Getting the call up to the big leagues

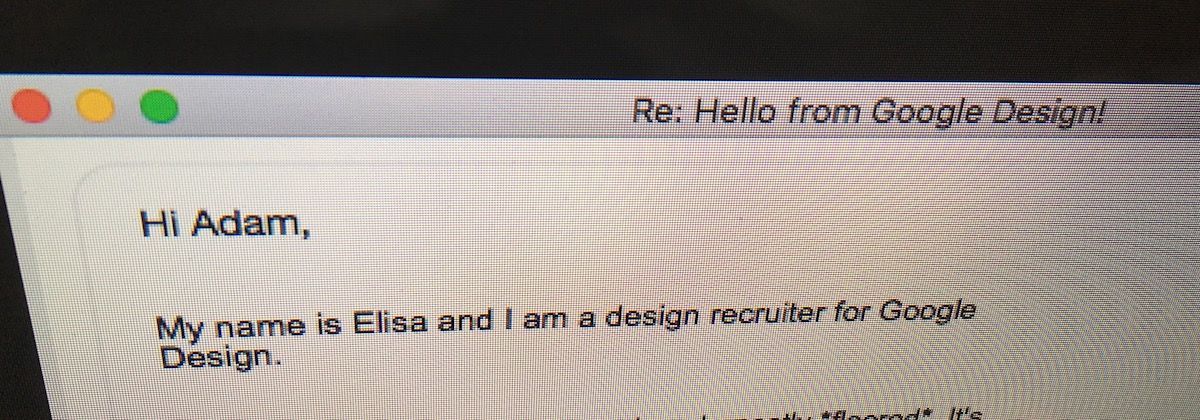

Freelancers get a lot of emails. Sometimes from big brands with amazing job requests and mountains of cash. This has never been my experience so I’ve learned to be very skeptical of emails from large companies. In the fall of 2015 I got an email from a recruiter at Google looking for a UX Motion Designer to work on Search and Maps. I was unsure about it since my long-term goals didn’t focus much on full-time work.

What could I actually contribute to a place like Google? I had zero experience in working with a team, or formal coding education, or any training in UX Motion Design. But I had no real training in normal motion design either, so maybe I could learn while I did it – like most everything in my life. Product design and usability were two major areas that I wanted to grow, so accepting the job was pretty obvious.

In January 2016, with the support of my amazing wife, we packed up our 2-year-old son and two dogs, sold our house in Atlanta and moved 2000 miles away from family and friends to start a new chunk of life working at one of the most desirable companies on earth.

Working at Google

I don’t have a lot of (or any) employment experience, but I know that Google is not like any place else. The enormous campus is filled with some of the smartest people on earth solving insanely complex problems every day. If you’ve never experienced Imposter Syndrome, this is a great place to do it. I had been paying the rent by drawing pictures and hacking together videos to sell sugary cereal, and now I worked next to PhDs in fields focused on developing the future. I was truly the dumbest person in the room in every room. But it was good.

For the first time in my work, I wasn’t fighting against budgets, or sponsors or CEOs clinging to an awful logo their nephew had designed. I was encouraged to push and test things. Visual designers factored in my concerns for motion while they set up screens. High-level decision makers listened when I described pitfalls and alternatives to existing solutions. Working directly with engineers was allowed and encouraged in order to create things that not only looked good but felt good too. This was my first pipeline where motion was not an afterthought to the production.

Working on a team with so many focused minds and strong opinions can be quite challenging, but it forces you to communicate with clarity and respect for differing ideas. It opened me up to evaluate my own design solutions more objectively than I have ever been allowed to. At times I felt compelled to fight for my idea, and the culture supported this dialog. Other times I recognized a teammate’s solution to be stronger and I was free to redirect my energy to support them and help elevate that idea. I had never experienced this way of working, and it was very encouraging.

Learning from experience

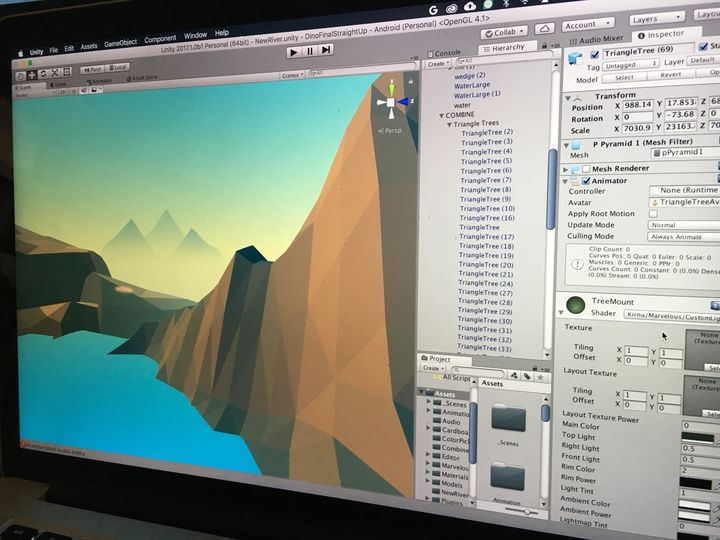

Learning is a major part of the culture at Google. Aside from programming, leadership, and meditation classes, there are giant growth opportunities everywhere. One day, while walking to get coffee, I caught someone working in Unity. A quick conversation connected me to a team in my department that was currently exploring concepts for what VR could mean in education. I had been curious about game design for quite a while but never found the time to really explore it. A quick conversation with the team-lead secured me 2 months of nearly uninterrupted training and exploration in Unity to help build out the project.

My favorite things that came out of this time:

- Lunch with Jane Ng shortly after she wrapped Firewatch just to pick her brain about working in Unity and scene design. The most focused brain dump in my life.

- Contracting Dave Chenell to blast the design of the project to a much richer place. I learned so much about shaders and coding in C# through the process. Later that year, he moved out to work with us full-time and has since become a good friend IRL.

Google resources provided me some of my most rapid growth opportunities simply by being open to them. At a company this large, there are unsolved problems that can align with almost any interest that a curious person could have.

Tool building for screen design

As I became more comfortable with the motion workflow at Google, I began to notice several major productivity gaps. Anyone who has ever tried to mock up a screen interaction in After Effects knows how tough it can be to replicate something non-linear on a timeline. Since motion is such a new facet of screen design, it does make sense that the tools and methods of working are not as mature as with engineering or visual design. I was hired to think about users as much as possible. By shifting my perspective to animators and interaction designers as the user themselves, it could hopefully allow them to bring more focus and energy to designing the end user’s experience.

A major skill that all successful freelancers develop is recognizing their own value and finding ways to sell that value to clients or markets that need it. Because this was such a need for our team and the larger motion design community at Google, I was able to spend the majority of my time building tools for animating the cute little colored dots, the complex effects of LED lights on Google Home, and a whole lot of other little time savers. The two biggest tools I worked on are now open source and free for anyone to use.

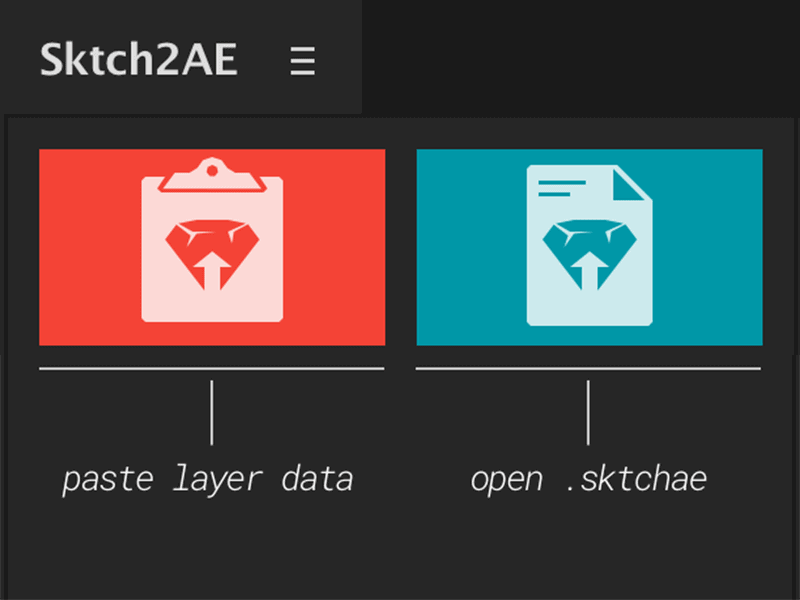

Sketch2AE – Sketch has arguably become the industry standard for screen design, but it is unable to export a layered format that works well with After Effects. Until now the only workflow was exporting every layer one at a time or redrawing the whole artboard in Illustrator.

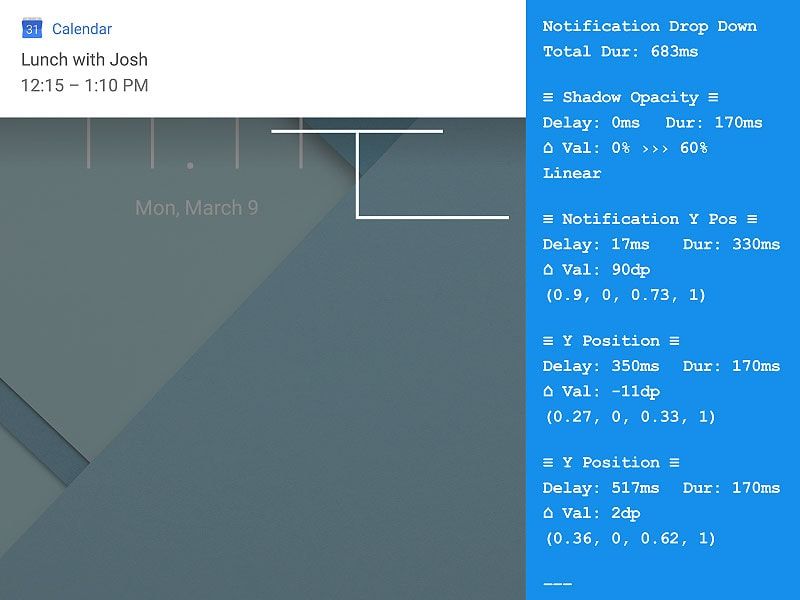

Inspector Spacetime – Engineers and animators use a lot of different terminologies when trying to communicate the same things. To improve this dialog, you can now quickly burn transformation data (in a clear text format for any codebase) onto the side of a QuickTime. This gives visual and data reference for how timing and curves are set up.

Everything is awesome until it isn’t

By August of 2016, I had adjusted to giving part of my day to meetings. My 3-year-old son Max was starting back to preschool and we were enjoying our weekends in the unbelievable nature of northern California. I was spending my daylight trying to understand what a career path actually was, and spending nights designing the second version of RubberHose. Out of nowhere, my wife Ashley casually mentions that her feet felt weird and tingly. During the next two weeks, she became uncharacteristically slow and began to lose coordination and balance. By the end of the month, she was unable to stand unassisted or walk for more than a few minutes.

Ashley visited every available doctor looking for answers and only one believed the problem might be more than the wild imagination of a hysterical woman. Because of this one doctor’s efforts, they found a set of spots on Ashley’s spine. While it was a relief to know that there was something real causing all the pain, discovering mysterious lesions on a scan at age 31 is pretty scary. Watching your partner go from highly active to losing the ability to pick up her son for a hug is awful. Up till this point, my biggest concern had been hitting rough deadlines. A real challenge like, “will my wife still be able to walk next week?” shifts your perspective quite a bit. The next month was spent in hospitals, MRI machines, having fluid drained from her spinal cord and every other test possible. Thanks to Google’s amazing medical insurance, Ashley’s mother flying out to live with us, and the scheduling flexibility of my team, we were able to get a diagnosis of Multiple Sclerosis. MS is a relatively uncommon disease where your immune system attacks areas of your spinal cord —screwing up the nervous system which includes walking and balance for many people. It affects everyone differently so finding the correct treatment can take a while.

Months passed with little improvement to her condition. I took a lot of time off to play a larger role at home for Ashley and Max. We flew back to Atlanta for Christmas and once there we realized that all of us returning to California would not be possible. We planned that I would return and get back to work and they would remain with family. We expected that after regaining some strength she and Max would fly back and we’d get on with our life.

After 6 weeks on opposite coasts and several red-eye flights, we decided that all of us being close to the rest of our family was the most important step we could take toward giving Ashley a chance at finding a manageable state. I’m unbelievably thankful for the opportunity to spend a year at Google. It really is an amazing company to work for.

What’s next?

We are currently figuring out what our new version of normal looks like. We have good days and bad, and the priority of my time and energy is (for the first time) on my family over my work. I’m incredibly thankful for the generous support of this community that has given me an opportunity to work on my own projects and at a slightly different pace. A more spaced out workday that fits around the needs of my wife and son, and allowing me to take some time away from client work.

Encouraging positive growth in my own health has become a part of my daily routine. Stress took a major toll on my body over the past year so now I’m finding ways to reduce stress and live a long time. I eat a mostly plant-based diet (even though I really love BBQ). I take an hour out of most days for strength training, spin class, stretching and breathing. I am starting to sleep a little bit more.

Two years ago, I didn’t write any code beyond small expressions, but now I’m a full-time developer of animation tools. I just finished a new system for connecting After Effects and Illustrator called Overlord and I’m looking forward to exploring and building new ways to work with motion design and animation. I’m incredibly grateful for the support of this industry and so thankful to be a part of it.